Transformation in Bhutanese Society: A Layman’s View

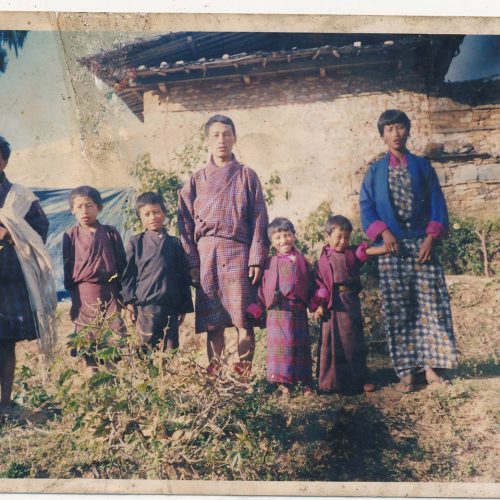

The waves of development have turned the tide in Bhutan. Interpreting development as an improvisation and advancement of a certain thing, its impact has been felt in all areas, viz. politics, economy, culture and the society as a whole. From democracy to mixed economy, and the changing habits of daily lives in the areas of food habits, dresses and expressions, forces of development have reached in all spheres and in all walks of Bhutanese lives.

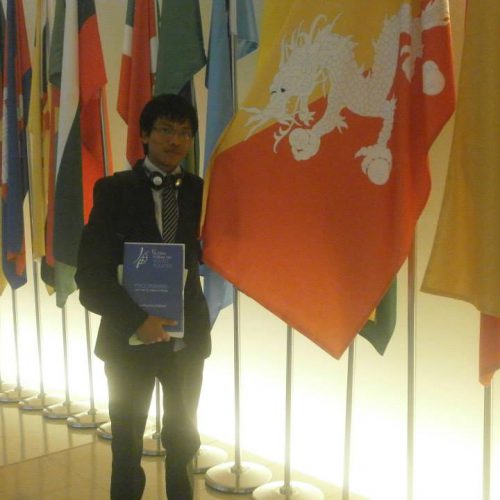

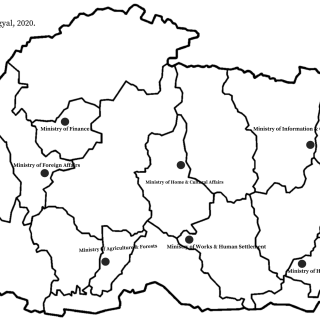

On the political front, institution of democracy has opened up a system of governance bringing those rulers ever closer to the ruled. Transparency and accountability have been the hallmark of the system while ensuring maximum people’s participation starting from voting to decision making. On the other hand, party politics and hunt for votes have divided communities, neighbours, friends and families on party lines, thus, building foes in place of fraternity.

Our economy has transformed in form as much as its size. Bhutan’s transition from being a pastoralist and barter economy to a modern economy is testified by its transactions of recent decades in Information Communication and Technology (ICT) products and hospitality services. The reverse effect, though, has come in the form of closure of household production of goods, say mustard oil, dwindling of the fate of cottage and small indigenous industries and local delicacies.

In the spheres of culture and aesthetic expressions, the change has been significant. The constant modification of the Gho and the Kira to fit the Bhutanese perception and changing times, coupled with our involvement in festivals and rituals, can hardly be attributed to our civic responsibility to preserve or be part of them; instead, the historical significance the culture and traditions play has led to such modification and change. As the rural setting give way to urban structure, the biggest change is seen in our architectural design – from dovetail techniques and mud houses to quality – tested concrete buildings. The growing popularity of night clubs in the urban centres, the decreasing practices of night hunting in some rural pockets and a reduction in the number of speaking lingua franca, Dzongkha, among literate lot are viewed as some of the changes that have come about over the years.

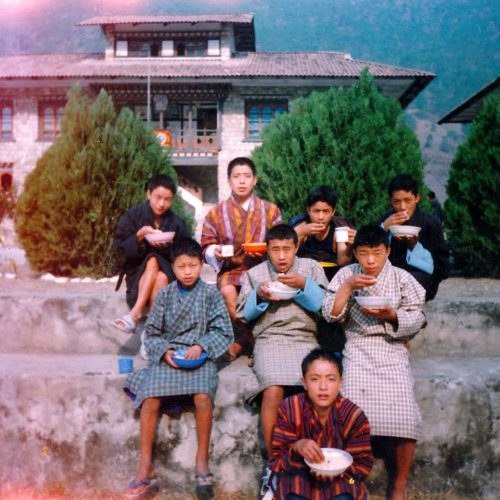

Telecommunication and transportation have been the biggest drivers of development. Mobile phone connectivity, access to internet and the installation of telex and postal services coupled with road and aviation connectivity – have sped up the delivery of goods and services both within and outside the country. With the exception of few remote parts of the country, the olden – day practices of messengers running errands of their lord and using ponies as a means of transportation have also declined. Specifically, television – through news, entertainment programs and advertisements – has brought the outside world ever closer. One immediate effect we see is the obsession of our kids to cartoon series and video games, while folktales of ageing parents go unrecorded.

Our consumption pattern over the last decade has seen a significant shift. The increasing consumption of fast foods and fizzy drinks has resulted in the near extinction or non – existence of our traditional consumption habits like foods made using the flour of barley, wheat and buckwheat; also, the usage of traditional cookeries like pots, Zaru and Zencha (ladles) has declined in rural corners, let alone in urban centers. The immediate effect has been a decline in the number of blacksmiths and artisans across the country. The ever – convenient plastics have dislodged the role of fig and banana leaves, which were once commonly used for rolling butter and cheese. In the same vein, hot cases, flask, plates and mugs have made the usage and utility of bangchung, torey, dapa obsolete.

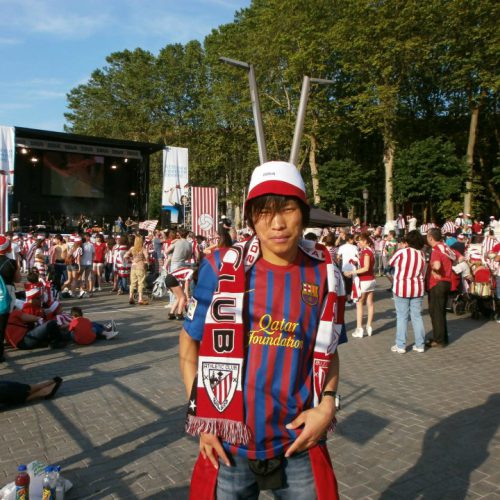

Much has been changed in the sphere of games and sports, too. While archery continues to be the dominant game – partly due to it being the national game of the country – the zest for football is on the rise, particularly among the urban dwellers and those coming through the modern education schooling system. Other games that have found its place among the Bhutanese include basketball, badminton, tennis, volleyball, carom, snooker and cards. On the other hand, games such as khuru, doegor, soksum, jigdum and pungdo are left on the fringes; Khuru, though, is still an exception to this. Archery also has undergone considerable change, as the number of people using compound bows and arrows has increased exponentially.

The introduction of modern education has brought about changes in societal views and ideologies. Individualism, capitalism and feminism has all established their roots in the country. Individualism and capitalism, for example, have instilled in values like self – confidence vis-à-vis entrepreneurial instincts. Similarly, the drive for profit-making has also resulted in rural folks venturing into Hazelnut plantations. The increasing emphasis on equal rights and the empowerment of women coming forward in all spheres, from academia, diplomacy and politics to sports. Conversely, individualism – in a way – has loosen ties among families, neighbours and communities; the ubiquitous sighting of beggars and the unattended elderly in bus stations and similar areas are a case in point.

From schools, hospitals and Renewable Natural Resources (RNR) centres in far flung rural areas to well-maintained cowshed, toilets and dustbins put in place in hamlets, the transformation has been unprecedented. This has contributed to increased life expectancy and literacy rates, improved living standards and quality of life. However, with the growth of urban centres – accompanied by the forces of development – social problems in the form of pollution, unemployment, migration and rural depopulation (the phenomenon which is best described as Goongtong) are on the upward spiral.