Physical distancing as a defence against COVID-19: What can Bhutan’s traditional and cultural norms offer?

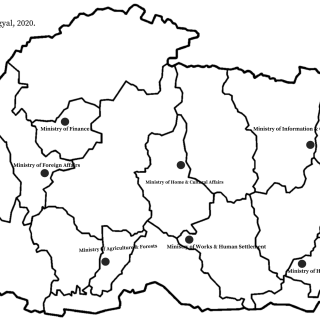

“Oye Oye, Stay Home; Oye Oye, Keep Distance”, the Minister for Health launched advocacy materials on ‘Physical Distancing’ today (23 April 2020). Developed on the command of His Majesty the King, it was a collaborative effort between the Ministry of Health and militia volunteers of 2003 low-intensity military conflict. The advocacy package contains a short music video, jingle and posters.

Poster on physical distancing. PC: Ministry of Health’s Facebook page

Poster on physical distancing. PC: Ministry of Health’s Facebook page

A veteran observer and a blogger, commenting on the title of the music video, “Oye-Oye”, was heard saying, ‘it sounds quite uncourteous’. A volunteer involved in conceptualising the video responded, ‘people need to be cautioned. Otherwise, they wouldn’t listen’. The observer nodded in agreement.

Prior to that, Her Excellency the Minister in her opening remarks lamented on how ignorant and uncooperative people are. Citing an example of her visit to Centenary Farmers Market, she said people are found in large groups. On communicating with a vendor to develop a signage requiring customers to maintain a required distance (one metre), a vendor is said to have told, ‘the moment we tell customers to wait, then they would have left’. Sharing reactions from the jingle (of the advocacy package) which was shared with young people, she said, ‘they get excited but would not follow the messages the jingle conveys’. Enforcement and implementation are a big challenge.

Referring to Her Excellency’s example, a volunteer shared, ‘we found people in large groups. As we shot the video (when people saw pictures being taken), then they began to disperse’. This took me to another imaginary world and our conduct- meetings these days. We do hand checks/ handshakes and later during the meeting, we maintain a one metre distance. Latter, the pictures come out in social media posts and updates.

Can we learn anything from our own traditional and cultural norms?

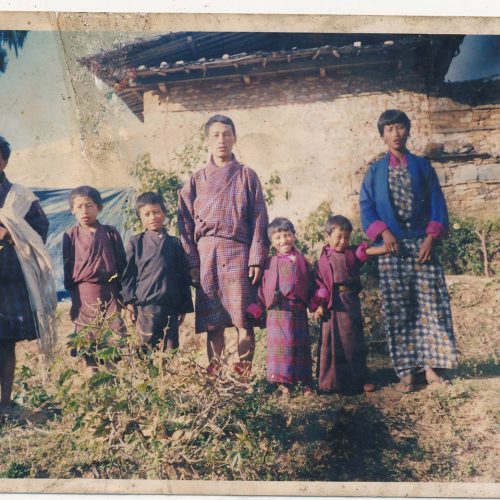

Bhutan is a closely-knit society. However, hugs, kisses and handshakes were not a means to greet and express our intimacy. Some time in 2005 as the new academic year commenced (at Gyalpozhing Higher Secondary School), coming across me shaking hands with considerable number of friends who had just reported to the school, a distant relative (who was accompanying her daughter), was simply amazed to see intimacy among friends expressed through handshakes.

Handshakes were unknown and unthought of, at least in rural hamlet of Drepung, Mongar. Instead, ‘a respectful bow with open hands’ were a medium to greet. Even to this day, it does not come into my mind to shake hand with my father and hug mother. Perhaps, my conservative outlook overweighs my openness influenced by westernization driven modern education. On the other hand, with friends, without handshakes and hugs, I feel my greetings incomplete. In the wake of COVID-19, as Dr. Karma Phuntsho puts it, it is the time we revive our greetings with ‘open hands and a respectful bow’.

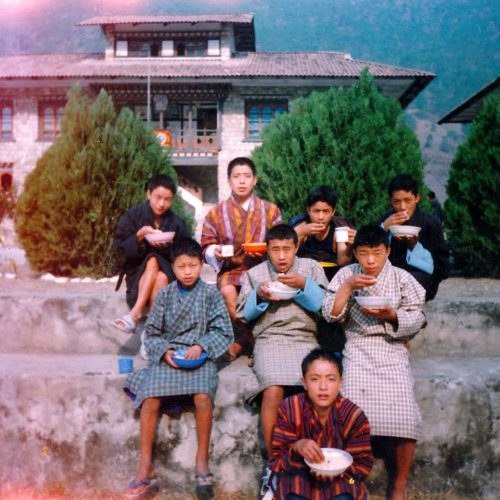

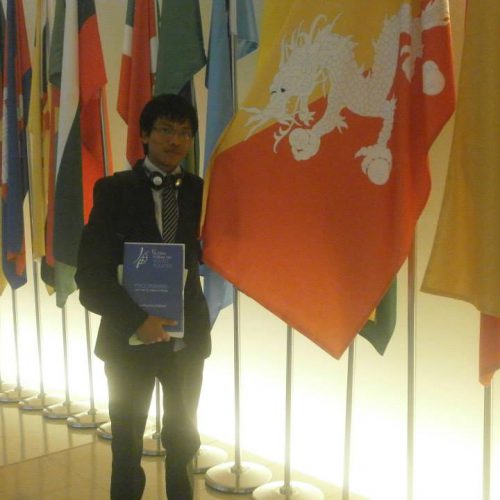

As a part of the advocacy materials launch, Venerable Tsugla Lopen’s video message was also screened. Emphasizing the importance of adhering with the government’s directive and its compatibility with Buddhist practices, Venerable Lopen drew some examples from Buddhist monastic life pertaining to physical distancing. For example, during prayer recitations and study, monks maintain a distance of handspan (gyi gang) and kab ji gang (equivalent to one metre) while in queue (or walking in a line). These practices form integral part of monastic discipline and etiquette. For a country like Bhutan where etiquette in social and public space is often used as a denominator to asses one’s personality; and the fact that much of our etiquette are drawn from our spiritual practices, cannot we be a little more disciplined.

Monks cross a bridge in a physically distanced manner. PC: Enchanting Travels

Monks cross a bridge in a physically distanced manner. PC: Enchanting Travels

Convergence of monastic discipline and modern ideology and practice

The concept of kab ji gang and gyi gang do have its application in westernization inspired modern Bhutan. The case in point is privacy. We have developed a tendency to get too close to a person while waiting in queue- groceries, automated teller machines (ATM) and hospitals to list but a few.

First, in groceries, people wait in queue leading up to the cash counter to the extent that the next person is able to see the cash in the wallet of a person paying the bill let alone the items bought. Near ATMs, people uncomfortably get too close that the person behind is able to see the pin code of the ATM card of the person withdrawing the money let alone the total cash withdrawn. In the hospital, particularly at the Jigme Dorji Wangchuck National Referral Hospital (JDWNRH), people wait in queue holding their health books and prescriptions. The moment one gets closer to each other, we land up seeing other persons health status and medical history, inadvertently.

Who would want a stranger know his or her medical complications unless the stranger is a physician? Who would want to let know others that the cash you are withdrawing from ATM is not more than Nu.100.00. Similarly, one may not like strangers or second person to see oneself asking for a discount or thin wallet at the cash counter of grocery stories or garment shops. One may not adhere with what seemingly looks like a strict observavance of monastic discipline; but one certainly should protect and respect another person’s privacy. In this social world where phyiscal interactions happen quite frequently, ‘physical distancing‘ is one way, if not the most important, to respect another person’s privacy. In doing so, we can help prevent transmission of the COVID-19.

As the efforts to combat COVID-19 continues, the emphasis on ‘new norms’ and ‘new normal’ are much talked about. If we take time to rewind our historical past and its everyday lives, the insights would lie there.

Disclaimer: The conclusions drawn and interpretations made in the article are solely mine. In addition, the comments from the speakers are used simply to contextualise the meaning I want to convey. I haven’t double checked the quote with the speakers; therefore, it may not be the exact words and phrases the speakers spoke.