Agriculture and the economic recovery- Finding solution within

In the wake of COVID-19 pandemic, the Government launched the Economic Contingency Plan (ECP). ECP Series-I identifies three components, namely, Build Bhutan Project, Tourism Resilience and Food Self-sufficiency to rebuild health crisis induced economic stress. With the nationwide lockdown enforced and economy rendered standstill, villages apparently are the only place where economic activities are still pursued, albeit with less rigour. As we ponder on pathways to navigate through the ongoing challenges, this article discusses the potential of village-based agriculture practice in the context of food self-sufficiency as envisioned in the ECP as one of the solutions in rebuilding the economy. The arguments are built around my own exposure to agriculture practices of my village, Drepung, Mongar with focus on two commodities, maize and mustard.

Figure 1: A woman in her maize field. PC: https://kuenselonline.com

Under food self-sufficiency component (of ECP), a list of priority commodities such as maize (cereals) and mustard (oilseeds) are identified. Maize is one of the much-valued grains often associated with an epithet, Tsampa (Rinpoche). Besides its utility as a staple food, a significant amount of maize is used in brewing alcohol (Ara). Ara in eastern Bhutan is very popular to an extent that one would be surprised if a sharchokp says he/she is a teetotaller (non-drinker). The concomitant effect of such trend is, at the national level, Alcohol Liver Diseases (ALD) consistently ranks top in the mortality rate. From a total of 1,264 death reported in 2019, at 11 per cent, ALD related death topped the list, yet again. It has two visible implications. First, hard-earned harvests are not put to effective use. Second, even worst, it is a cause of one’s own complications, possibly premature death.

We (Bhutanese) proudly claim, ‘rice is the staple food of Bhutan’. Even certain school textbooks propagate such an idea which I do not agree because I am Bhutanese and rice wasn’t my staple food until I moved out from the countryside Drepung. Ironically, in 2019, we imported Nu.1.7 billion worth of rice -the so called ‘staple food’- the 5th highest imported commodity in terms of value. While we are assured that there are adequate supplies for the next six months, we should also think beyond COVID-19.

Figure 2. Sweet buckwheat in full bloom in Bumthang. PC: MoAF

Figure 2. Sweet buckwheat in full bloom in Bumthang. PC: MoAF

Even in immediacy, we may find alternatives within- provided we choose to. As farmers prepare to harvest maize, in a month or two (from August), perhaps our planners and field officers can explore modalities to convert those maize production for commercial sale. In doing so, it would have twin visible benefits. First, farmers would earn income. Second, even grander, it would help us move towards food self-sufficiency/food security. Market? My friends and colleagues from non-maize growing Dzongkhags use to like Kharang and cornflour. Hopefully, they and some others will continue to. If a modality can be worked out, it can be replicated beyond COVID-19 pandemic.

As autumn peaks, barley (local term phe mung) will be sown. Mustard grows on its own alongside barley which is treated equivalent to a weed. Once mustard begins to flower, it is uprooted to feed cattle. Occasionally, mustard (leaves) are harvested for sell or to dry (vegetable for off season). The downside of current practice is, at least as I see it, barley is solely used for brewing ara with exception to an insignificant amount used for preparing dough (for rituals and rites).

During those yester years, when my grandparents and parents did not know such an essential item by the name ‘refined mustard oil’, we used to process our own mustard oil at home. It was quite labour intensive and the process rudimentary though. Had COVID-19 or similar pandemic struck us then, we would not have worried as much as my parents and sister do today- because we are dependent on businesses in Mongar and Gyalposhing who indeed have to rely on transporters to reach from Phuntsholing or other bordering towns and beyond. At hindsight, we gave in easily to simpler and easier task making us more vulnerable and insecure in the process.

With international borders sealed and transmission of COVID-19 during transhipment a possibility, we are compelled to look in our own backyard. In a way, it is a timely reminder! As we sail through these trying times, we can consider the following:

In immediacy (one to five months),

- The government (through the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests and State Owned Entreprises) need to explore ways through which utility from maize harvest can be optimised and mustard oil extraction/production refined to support our food security goal. Further, local (traditional) cereals are found to be nutritious and having curative power. Kharang is said have cured diabetes. Quiona because of its rich nutritional content is often referred to as a ‘superfood’. Attributable to its nutritional value and potential to fight hunger, the United Nations declared 2013 as the International Year of Quinoa.

- The Local Governments as the nearest state machinery to farmers, need to create awareness on opportunities of agriculture produce and how it would help in achieving national goals. Apparently, the policy initiatives as laid in the ECP hasn’t reached people in my village. Perhaps, Mongar is not one of those focus Dzongkhags.

Figure 3. Quinoa. PC: https://www.talkplant.com/bhutan-can-grow-quinoa/

In the long run (one year – three years),

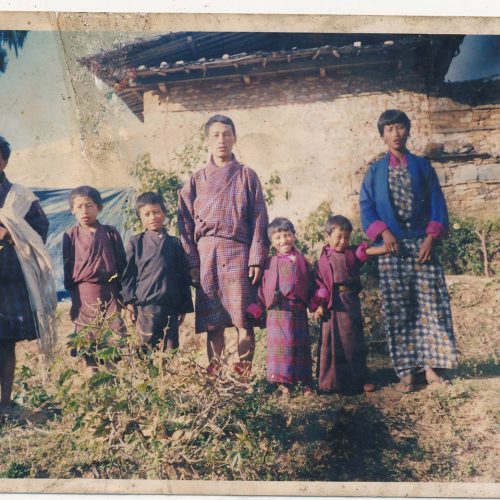

- A comprehensive study needs to be undertaken to revive traditional grains. It would help diversify our diets, amplify food security objective and help preserve old age agriculture practice. In less than a decade’s time, sweet buckwheat and wheat are no more grown in my village. At this rate, traditional cereals and associated heritage will be lost.

- School Agriculture Programme (SAP) should help younger generation learn about rich agriculture practice which propelled self-sustaining economy during our forefathers’ time. Taking students on field trips to the state run farms and lessons on commercial farming do not adequately ensure historical continuity. Traditional knowledge such as oil extraction from certain plants are fast disappearing. Cereals such as lha sa ma (quinoa), che ra, yang ra, mo (all local (tshangla) terminology) etc can only be heard during conversation among elderlies not in the school textbooks and menu. Modernisation is not abandonment of the past but refinement of it.

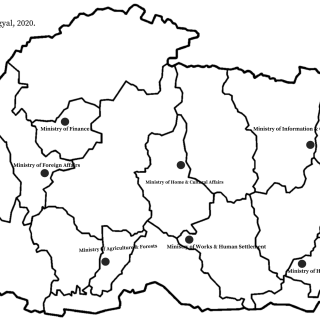

- Farm works are very labour intensive but unpredictable. Supplementing current support from the government, subsidies and crop insurance are some of the areas that might help retain people in the agriculture sector. Equally important, access to market is key [relocate government offices] – take consumers (people) closer to the suppliers (farmers). Otherwise, a significant amount of earnings from farm produce would go to intermediary (brokerage) leaving minimal amount to farmers who toiled the soil.

I do not claim these set of recommendations as something new- perhaps, we did not act adequately on these ideas before. At the same time, the aforementioned recommendations are neither a product of scientific inquiry nor a data driven propositions. These are opinions formed based on lived stories – as Henry Kissinger exclaimed, “history teaches by analogy.”

PS: As you reminisce your village experience, if any, and reflect on our dietary choices and habits then (and now), please provide a list of food grains in your communities. This will help us compile a comprehensive list of cereals, oils seeds etc for further study and share with relevant stakeholders. Local terminology are also encouraged for I acknowledge that I do not know English terms for most of the cereals that my parents grow, today.

Wow! Well said and written Dechen.

True that these recommendations are not new but failed in implementation.

I hope this article reaches the appropriate relevant agency.

Talking about it all the time is the most important and I am glad you wrote about it just in time – as we become contributors to the economic road map.

I believe 🙂 you will raise this later 🙂

Nicely narrated

Indeed thoughtful recommendation Ata. It was nice to know the Agricultural practices of my village Drepung. I would love to see the long lost agriculture practices come into practice sooner!

Happy to know that I share same village with you! I would love to see you one fine day Ata!

Greetings from Trongsa!

I agree with you la

The cereals grown in proper Haa are

Wheat – kaa

Barley – NAA

Sweet buckwheat – gayraay

Bitter buckwheat – bjoo

Mustard – peeks

Amaranth – aiiem

Quinoa

Both corns (popcorn & non-popcorn)

Millet – meemja

Of course rice in Gakling Dungkhag

Well writen article sir. Such idea would surely help in bringing economic stability or prosperity but i would suggest to put health and scientific benefits in your work as these are the important matter taken by general masses these days.

Let us all prepare for the future, before the hunger hit us. Like author mentioned we would love to practically see our bhutanese age old cereals to grow again and maintain no food crisis.

Note.

Enjoyed reading the article with full of insights laa…

Maize is ultimately an imported crop – it is native to Central America (Mexico) where it was domesticated 9,000 years ago and was only brought to Europe at the end of the 15th century – from Europe it then spread to Africa and Asia.

Growing Maize depletes the soil of nitrogen. It should be grown together with beans or pulses which put back nitrogen into the soil. In traditional cultivation maize provided support for bean plants and the beans provided nitrogen derived from nitrogen-fixing rhizobia bacteria which live on the roots of beans and other legumes and squashes or marrow were also grown together to provide ground cover to stop weeds and inhibit evaporation by providing shade over the soil.

The nutritional value of maize can be greatly enhanced by a traditional process known as nixtamalization where the maize grain is treated with limewater (water mixed with calcium hydroxide or tsuni). This unlocks proteins and niacin (vitamin B3) in the cornmeal, making it more nutritious for the consumer. Is also makes ground maize tastier and easier to digest. Eating maize-based foods without nixtamalization or supplementation with legumes, pulses or meat leads to a nutritional deficiency disease known as pellagra.

Maize also has suboptimal amounts of the essential amino acids tryptophan and lyssine, which accounts for its lower status as a protein source. However, the proteins of beans and legumes complement those of maize so these should be eaten together for balanced nutrition.

Flour made from nixtamalized maize can be used to make tortillas (maize roti) and many other foods.

Well, as sir has rightly pointed out and opined, it seems that most of what our Bhutanese citizens call rice as a ‘staple food’ is a bogus. Also, I strongly agree to your assertion that much of the tradional methods in which cereals are cultivated are on the decline. To put this into perspective, I, myself am hailing from the Eastern Dzongkhag and though I haven’t been able to stay in the village for very long, I have a certain knowhow of what traditional cereals used to be grown by the farmers in my village. My village, for the most part has been reliant on maize. To the best of my experience and knowledge, not very long ago, the farmers in my village used to grow diverse cereals such as those mentioned by sir viz. Yangra and so forth. However, in the current scenario, I don’t find many villagers, if any, growing a lot of such inherent cereal crops. Back then, most of the fields would look aglow with mustard, buckwheat, wheat, millet, and so forth, but currently, such enthralling scenes are not a commjn sight (sad to mention though). Considering all these transformations, I can come to a similar conclusion that it appears to be so true that indeed, traditional cereals are diminishing. Now, as well all know, our country is not self-sufficient in food. In other words, Bhutan is largely reliant on importation for most of its dietary needs, creating negative trade balance. The ECP, however, launched by the RGoB sparks a beacon of joy which includes food self-sufficiency as one of the top priorities. I am of the similar view or opinion that yes, the government and the relevant stakeholders really need to emphasise on reviving the age-old cereals against what would come as an utter extermination in the near future la. This way, I do believe that Bhutan can diversify the nutritional intake of cereal crops. We can’t afford to always depend on the branded rice commodities like RajBog etc for too long, given food security as our highly positioned vision. Just my opinions la.